Introduction to Smart Contracts

Smart contracts are programs that run on top of a blockchain and encapsulate the terms of a contract to be executed when certain conditions are met. Smart contracts were first theorized by Nick Szabo in the

late 1990s.

Unlike regular Legal agreements, which require a trusted third party to mediate disputes and enforce the agreements, a Smart contract is self-enforcing. Legal contracts are open to interpretation. Smart contracts are written in code and interpreted and executed by machines.

A smart contract is a computerized transaction protocol that executes the terms of a contract. The general objectives of smart contract design are to satisfy common contractual conditions (such as payment terms, liens, confidentiality, and even enforcement), minimize exceptions both malicious and accidental, and minimize the need for trusted intermediaries. Related economic goals include lowering fraud loss, arbitration and enforcement costs, and other transaction costs.

...

Digital cash protocols are fine examples of smart contracts. They enable online payment while honoring the characteristics desired of paper cash: unforgeability, confidentiality, and divisibility.

Vending machines or ticket machines in a railway station can be treated as a simple example of a digitized contract. With the right inputs, a specific output is guaranteed.

- You select a product

- The machine returns the amount required to purchase the product

- You insert the required amount with the supported currency

- The vending machine verifies you have inserted enough currency

- The vending machine dispenses the product of choice

Smart contracts are inherently required to be deterministic. That is, it should be possible for any node on a network to run the smart contract with the same inputs and achieve the same result. The nodes should reach a consensus on these results.

So, essentially Smart Contracts are software that make use of blockchain technology to codify business logic and self-execute an agreement based on conditions they automatically detect.

Oracles

Smart contracts stay inside the blockchain, i.e., they cannot access external data, which might be required to execute some contract terms. An oracle is a bridge between the blockchain and the real world. An example is the security's stock price that the contract needs to release the dividend payments.

There are mainly two categories of Oracles:

- Standard or Simple Oracle: A centralized, reputable organization provides the off-chain data

- Decentralized Oracle: A decentralized way of receiving the off-chain data

Smart Contract Use Cases and Platforms

Applications of Smart Contracts range from finance, e-commerce, supply-chain, gaming, insurance, auditing, and taxation. One of the use-cases of Smart Contracts that the market is using vastly is Programmable Money, i.e., the conditions to transfer the money will be codified by the developers in the Smart Contracts.

Financial Security

Smart contracts could be used for liability management, automatic payments, stock splits, and dividends.

Digital Identity

Smart contracts provide individual identity in digital assets, remove counterfeits and also make KYC frictionless.

Trade Finance

Smart contracts could be used for cross-border payments and international trade without the intervention of Banks and governments.

Financial Data Recording

Smart contracts improve data recording and accuracy and save reporting and auditing costs using the blockchain as the database.

Supply Chain Management

Smart contracts could be used to automate supply chain management with visibility and transparency, leading to fewer frauds.

Government

Smart contracts could be used for elections, voting on policy proposals, and voting on passing new bills.

Insurance

Smart contracts could be used to automate claims and resolves disputes with proof.

Loyalty Points

Smart contracts and Programmable money can be used by organizations to reward their customers.

Escrow

Smart contracts are the perfect resource for implementing escrow accounts with Programmable money.

DAO

DAO stands for Decentralised Autonomous Organizations. Smart contracts lay the foundational rules and execute the agreed-upon decisions making DAO a fully autonomous and transparent entity. At any point, the community can review publicly audit proposals, voting, and even the code itself.

A brief history of Smart Contracts Hacks

DAO Hack

Members of the Ethereum community, at the beginning of May 2016, announced the inception of The DAO, which was also known as Genesis DAO. The DAO was meant to operate like a venture capital fund for the crypto and decentralized space.

The DAO has raised 12.7M Ether in the creation period ($150M at the time of creation, and approx $22 Billion in 2022). This is the biggest crowdfund ever.

The idea of the DAO is members could pitch their idea to the community and potentially receive funding from the DAO. Anyone with DAO tokens could vote on plans and would then receive rewards if the projects turned a profit. The DAO's business logic was built as a smart contract on the Ethereum blockchain.

However, on June 17, 2016, a hacker found a loophole in the coding that allowed him to drain funds from The DAO.

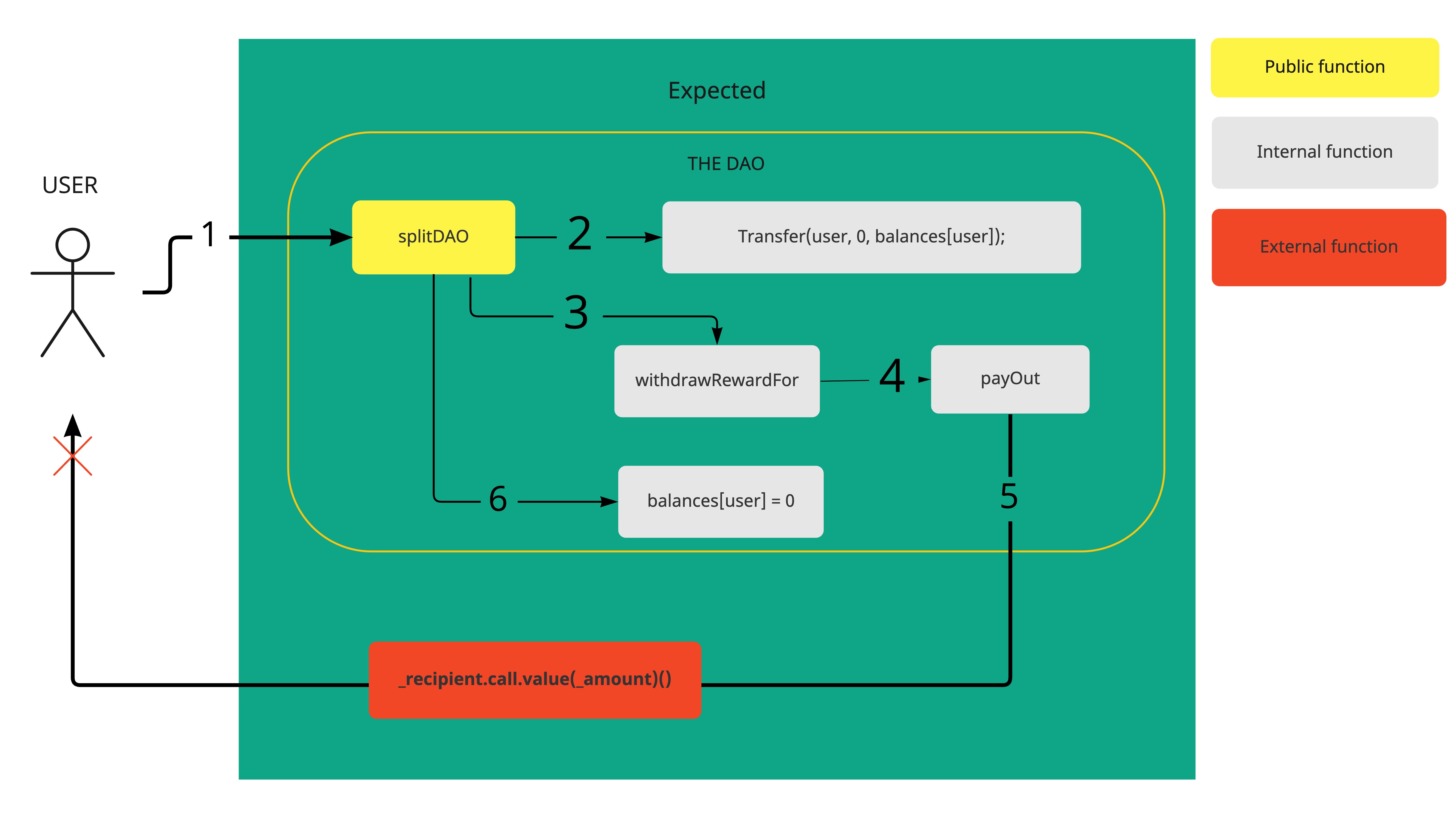

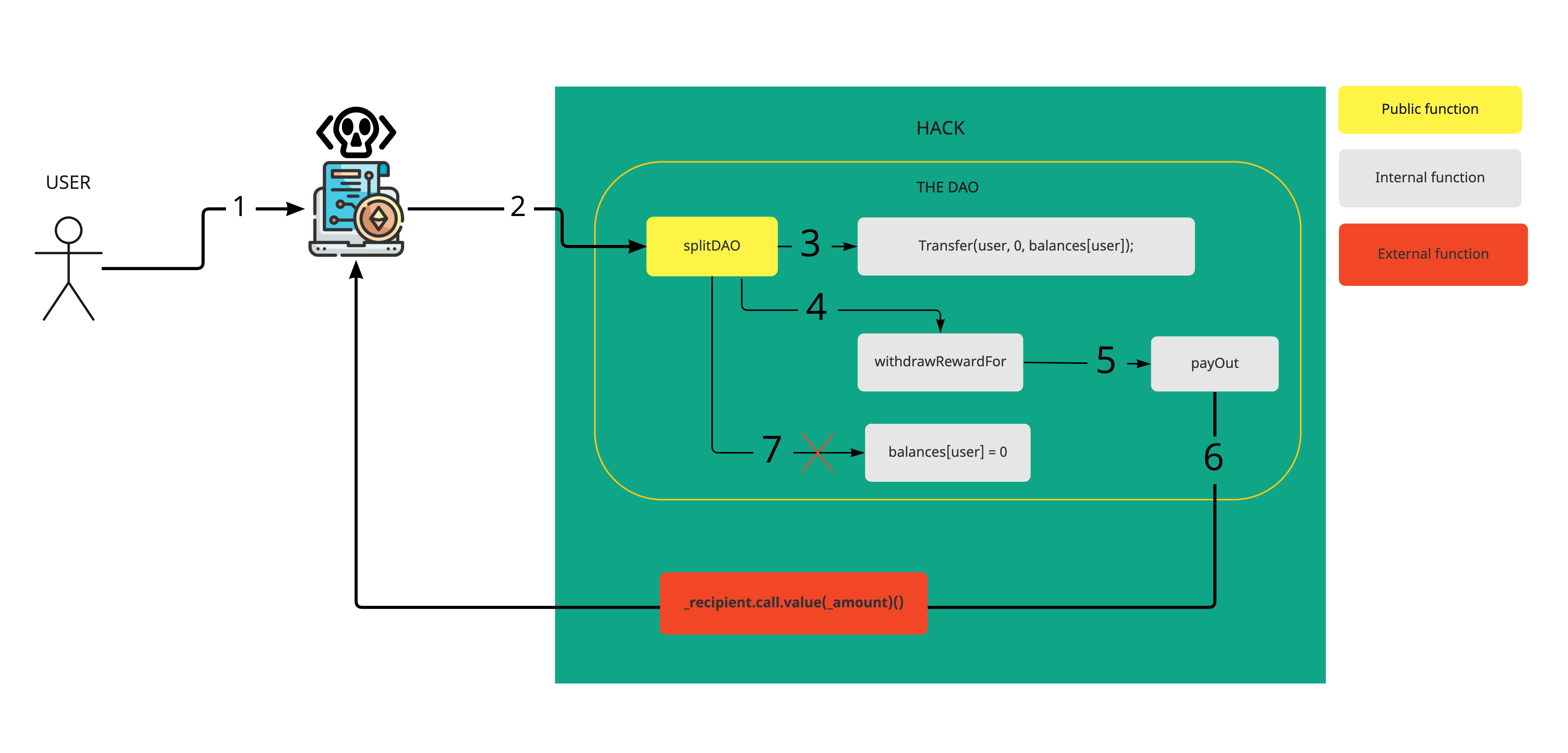

In computing, a computer program or subroutine is called reentrant if multiple invocations can safely run concurrently on multiple processors, or on a single processor system. A re-entrancy attack occurs when a function makes an external call to another untrusted contract and the untrusted contract makes a recursive call back to the original function in an attempt to drain funds.

function splitDAO(uint _proposalID, address _newCurator) noEther onlyTokenholders returns (bool _success) { ... // Move ether and assign new Tokens uint fundsToBeMoved = (balances[msg.sender] * p.splitData[0].splitBalance) / p.splitData[0].totalSupply; // @@@note: notice how this is done first! if (p.splitData[0].newDAO.createTokenProxy.value(fundsToBeMoved)(msg.sender) == false) // @@@note: This is the line the attacker wants to run more than once throw; // Burn DAO Tokens Transfer(msg.sender, 0, balances[msg.sender]); withdrawRewardFor(msg.sender); // @@@note: withdrawRewardFor -> payOut-> _recipient.call.value: re-entrancy vulnerability ... balances[msg.sender] = 0; // @@@note: Update the sender's balance after transferring funds to the user paidOut[msg.sender] = 0; ... return true;}function withdrawRewardFor(address _account) noEther internal returns (bool _success) { ... uint reward = calculateReward(); rewardAccount.payOut(_account, reward); return true;}function payOut(address _recipient, uint _amount) returns (bool) { _recipient.call.value(_amount)();}

Impact of the hack

To reverse the effects of the hack, the Ethereum community decided to go through a hard fork.

- Soft fork: A soft fork is a software update of a blockchain network that is backward compatible.

- Hard fork: A hard fork is a software update that is not backwards compatible. Might lead to network split.

The hard fork effectively rolled back the Ethereum network's history to before The DAO attack and reallocated The DAO's ether (ETH) to a different smart contract so that investors could withdraw their funds.

This is extremely controversial — after all, blockchains are supposed to be immutable and censorship-resistant.

Parity Wallet Hack

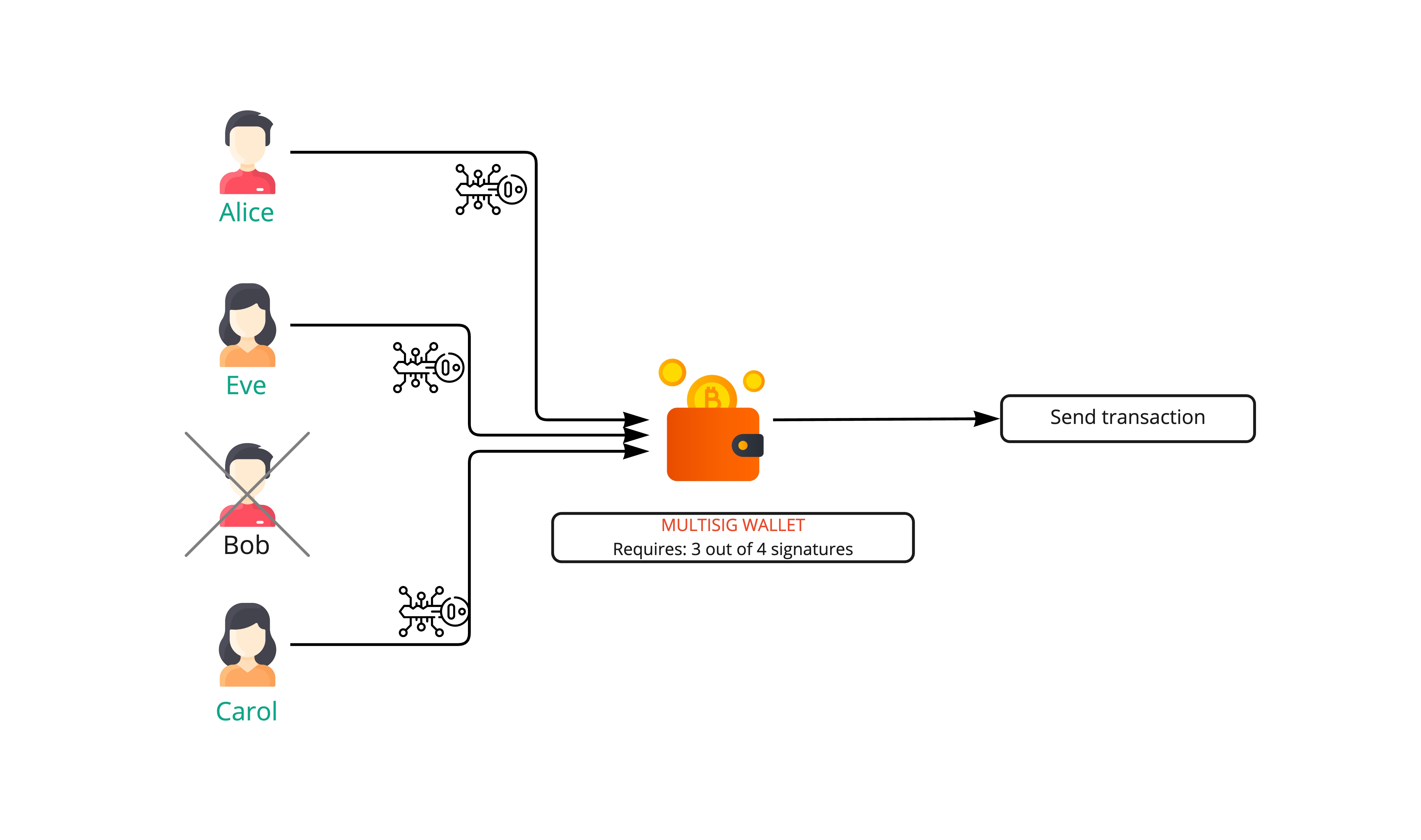

Multi-signature (Multisig) wallet requires multiple keys to authorize a transaction, rather than a single signature from one key. Usually, Multisig Wallets are implemented as a Smart Contract.

Parity technologies is a key infrastructure developer company in Ethereum. Parity Technologies made multisig smart contract wallets open-source and available for everyone to deploy and use.

Parity technologies is a key infrastructure developer company in Ethereum. Parity Technologies made multisig smart contract wallets open-source and available for everyone to deploy and use.

In 2017, a black-hat hacker used a vulnerability to drain the Parity wallets of three Ethereum projects, Swarm City, Edgeless, Aeternity, stealing a combined 153,037 ETH. These wallets were used to store funds from past token sales.

The bug, specific to the multi-signature contract known as wallet.sol, allowed the hacker to take ownership of a victim’s wallet with a single transaction.

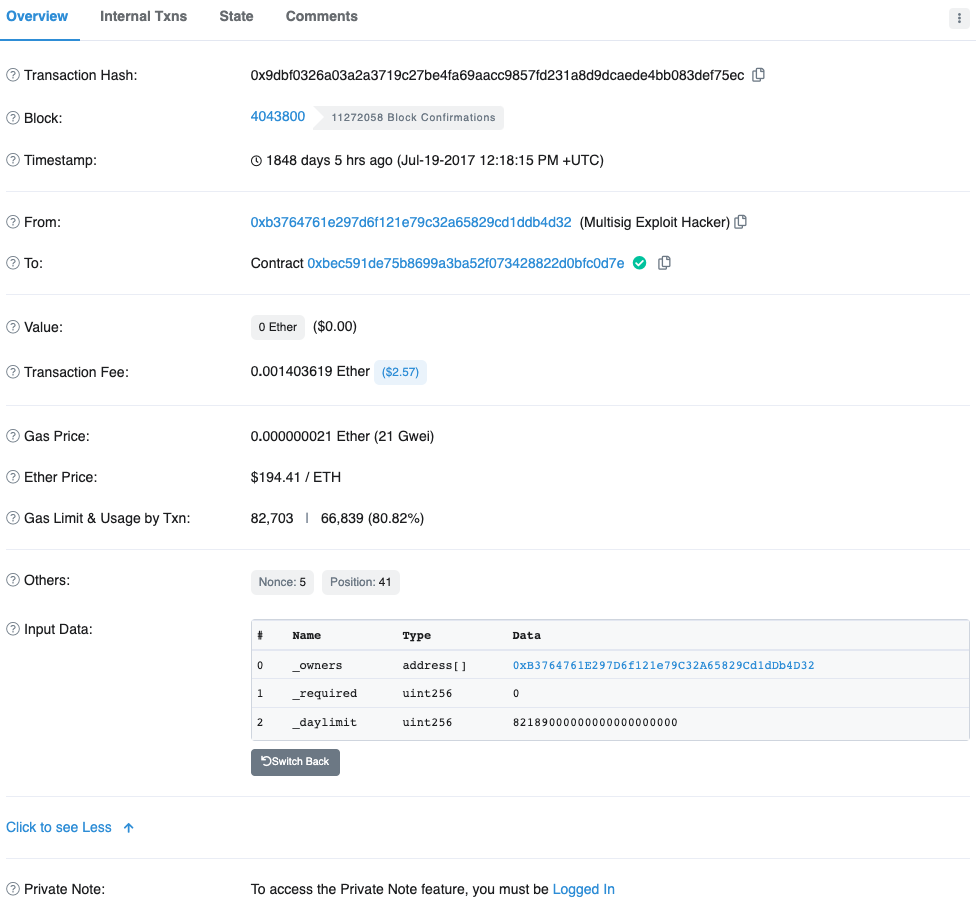

The attacker sent two transactions each to the affected contracts:

We can see that the first transaction calls initWallet function with 3 arguments setting the attacker's public key 0xB3764761E297D6f121e79C32A65829Cd1dDb4D32 as the owner of the contract.

Snippet of initWallet method from WalletLibrary contract:

The initWallet method seems to be a converted constructor method to make the WalletLibrary contract a separate library contract so once deployed. This pattern is referred to as the Proxy pattern, explained in detail here.

The proxy contracts usually just forwards all unmatched function calls to the contract behind the proxy, using deletegateCall. This can be seen in the payable method.

This allowed anyone to call all the public functions from the WalletLibrary, including initWallet, which can change the contract's owners.

Using this pattern, attacker managed to make his wallet's address as the owner of the WalletLibrary contract and managed to withdraw all the funds by calling execute

The Nomad Bridge Hack

Feb, 2022, a hacker exploited a vulnerability in Wormhole's smart contract code that allowed the hacker to mint 120,000 Wrapped Ether (WeETH) on Solana blockchain.

Wormhole is a communication bridge between Solana and other top decentralized finance (DeFi) networks. Existing projects, platforms, and communities are able to move tokenized assets seamlessly across blockchains and benefit from Solana’s high speed and low cost.

A Bridge is a link between two blockchains, basically a way to move crypto assets (tokens, NFTs) between different blockchains.

The way these protocols work:

- A user interacts with cross-chain bridge by sending funds in one asset to the bridge protocol (asset-origin)

- these funds are locked into the contract (asset-locked)

- The user is issued a equivalent funds of an asset on the chain the asset was sent to. (asset-mint)

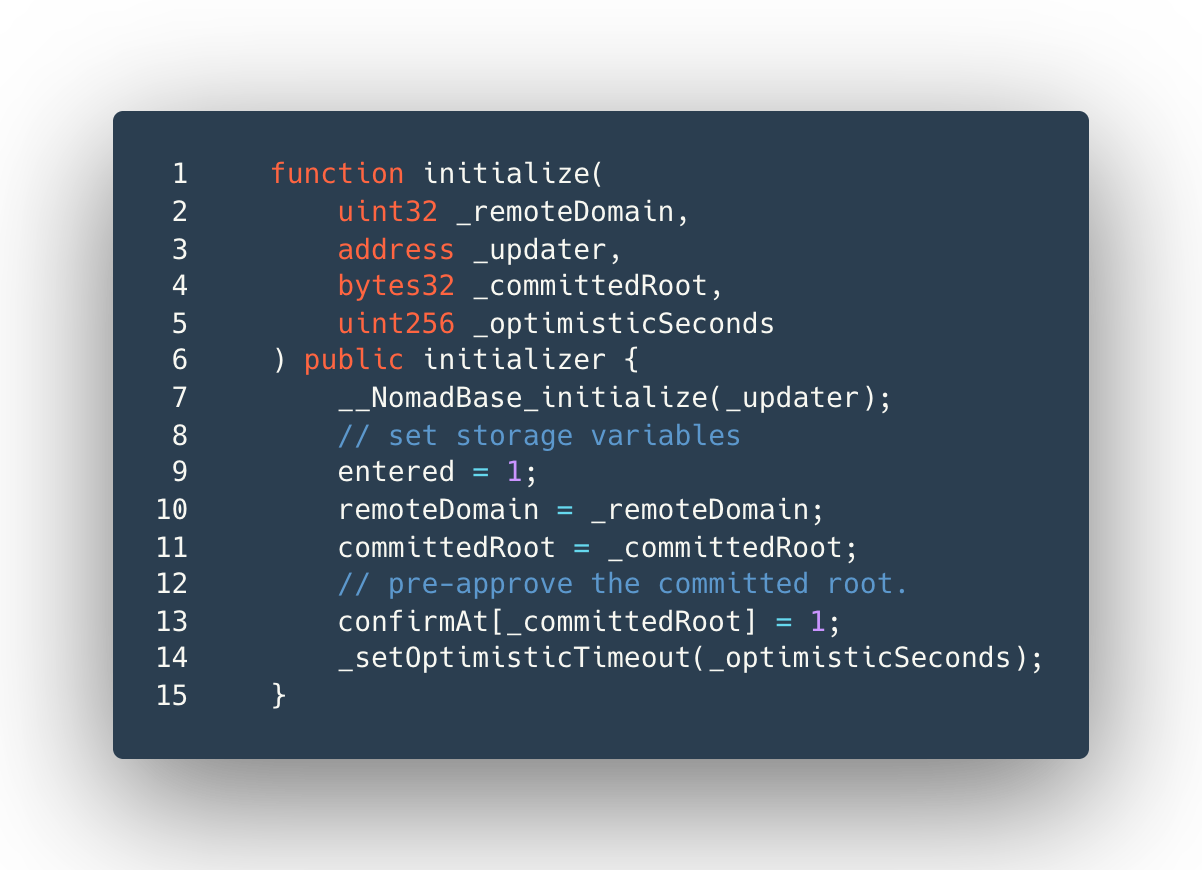

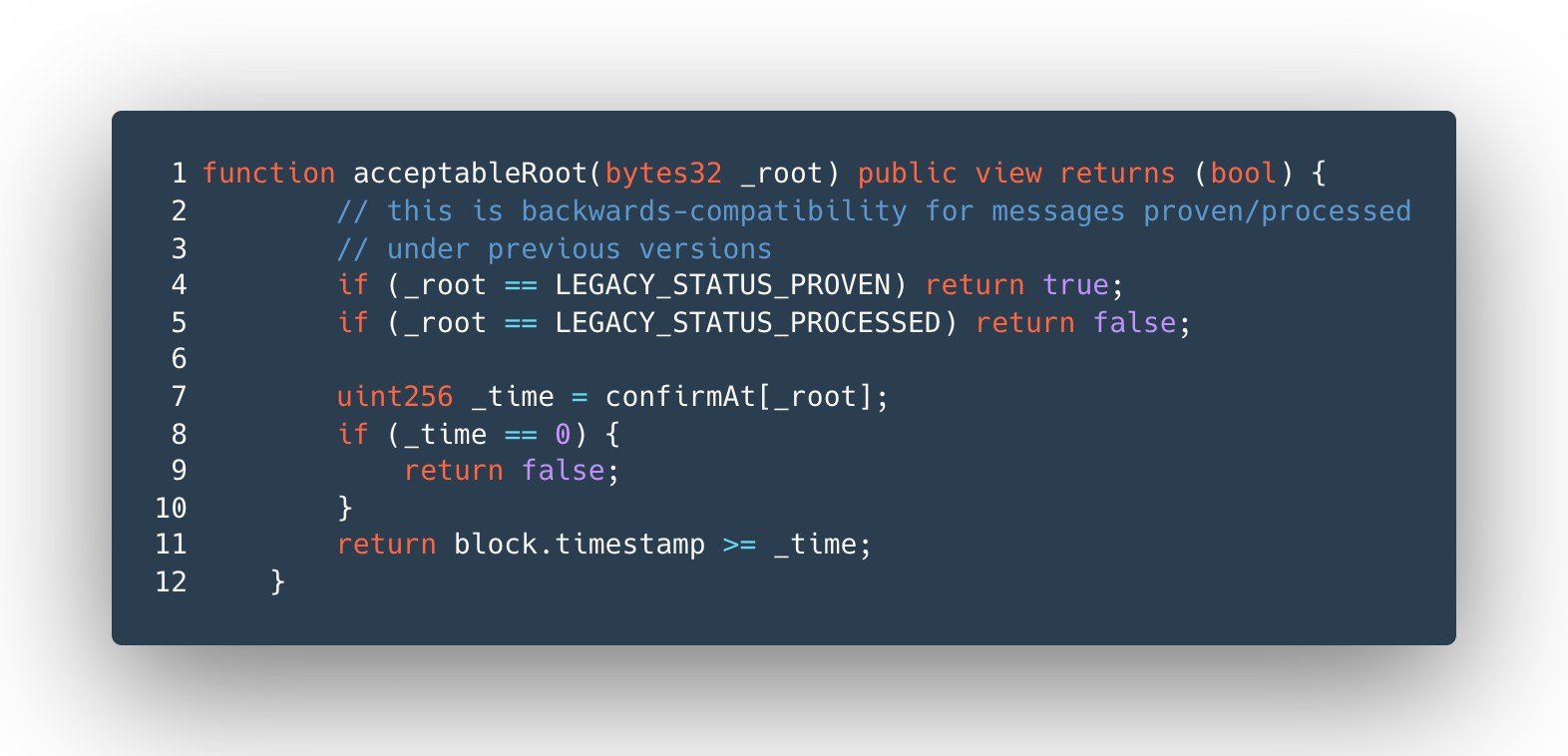

An implementation bug caused the Replica contract to fail to authenticate messages properly. This issue allowed any message to be forged as long as it had not already been processed. As a result, contracts relying on the Replica for authentication of inbound messages suffered security failures. This authentication failure resulted in fraudulent messages being passed to the Nomad BridgeRouter contract.

“... [Y]ou didn't need to know about Solidity or Merkle Trees or anything like that. All you had to do was find a transaction that worked, find/replace the other person's address with yours, and then re-broadcast it,” @samczsun explained.

Ronin Network Bridge Hack

The Ronin Network hack was a result of compromised private keys of the validators. Ronin Network uses a set of 9 validator nodes to approve transactions on the bridge. A deposit/withdrawal requires approval by a majority of 5 out of 9 nodes.

The attacker gained control of 4 validators controlled by Sky Mavis and a third-party Axie DAO validator, totalling 5 validators, that signed their malicious transactions.

References

- Smart Contracts - by Nick Szabo

- "DECENTRALIZED AUTONOMOUS ORGANIZATION TO AUTOMATE GOVERNANCE"

- Formalizing and Securing Relationships on Public Networks

- Oracles

- A chronological and (hopefully) complete list of reentrancy attacks to date

- Analysis of the DAO exploit

- Parity Hack

- [Wormhole]https://solana.com/news/wormhole---solana-ethereum-bridge

- Wormhole bridge hack

- Ronin Network Hack

- Nomand Bridge Hack: Root Cause Analysis